Light & Shade: The Cultural Politics of Black History Month

Authored By: dies0044 02/01/2021Reflections from Assistant Vice Chancellor of Student Success, Engagement, and Equity, Andrew Williams

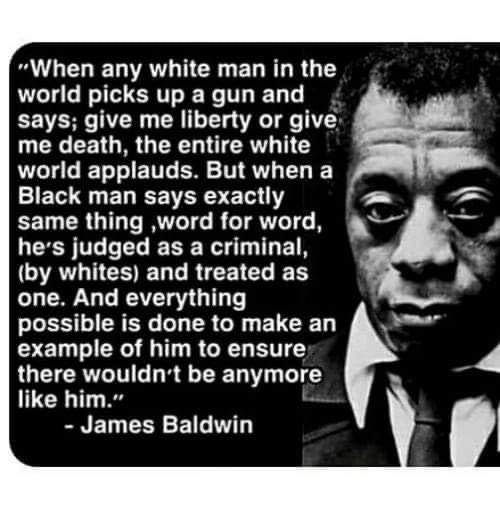

As part of a national pantheon of ethnic heritage month celebrations, Black History Month might be seen as a cultural marker that invites us to reflect on the history, culture, and politics of our nation’s vibrant and diverse African American population. The seminal African American cultural critic and literary giant James Baldwin has written that “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” This important insight has perhaps never been more apparent than over the last nine months of our lives.

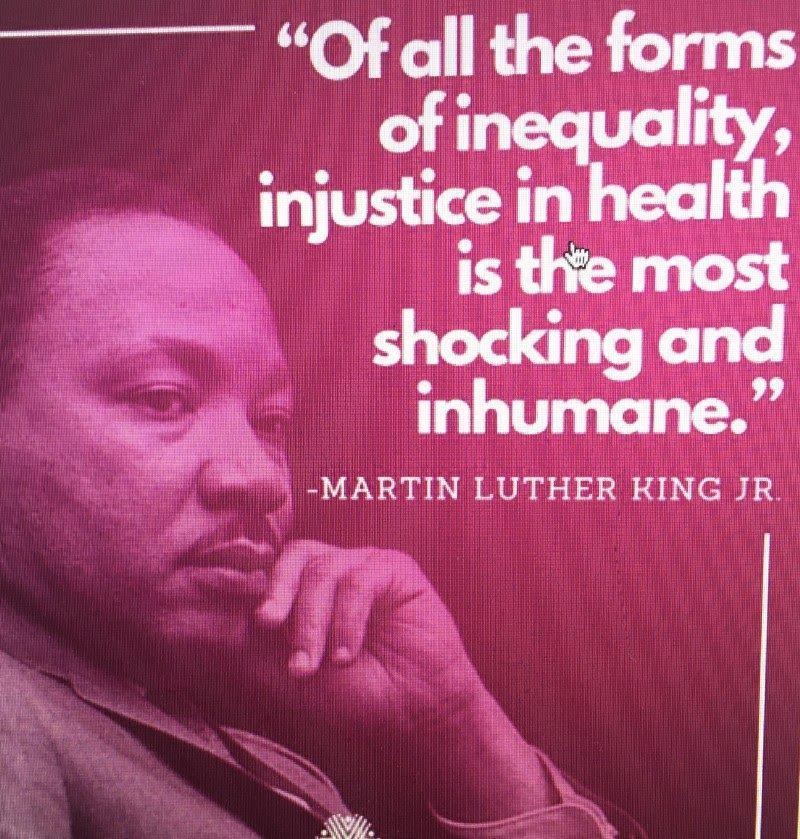

We see our nation’s history of state-sanctioned racialized violence echoing in the unwarranted police killing of an unarmed George Floyd and the violent repression of the racial justice protests it sparked. We feel the historical aftershocks of medical apartheid in the disproportionate rates of COVID infections and deaths among African American, Latinx, and Native communities. And if one knows how to read all the symbols that were on display during the recent January 6 assault on Congress, one can see the reflection of America’s history as a settler-colonial society violently founded on genocide, slavery, white supremacy, racial terrorism, and Christian nationalism. As an African American who grew up in a mixed Black and Jewish community, that included Holocaust survivors, the violent storming of Congress presented a disturbing mixture of Christian nationalist and racist symbolism amongst the rioters: there were Christian crosses and Jesus Saves banners, Trump flags, and American flags, fascist insignia and a ‘Camp Auschwitz’ hoodie. And for the first time in American history, the Confederate flag, one of the most potent symbols of white supremacy and sedition, was paraded through the halls of Congress. Finally, a gallows was set up on Congressional grounds to lynch targeted members of Congress and Vice President Pence.

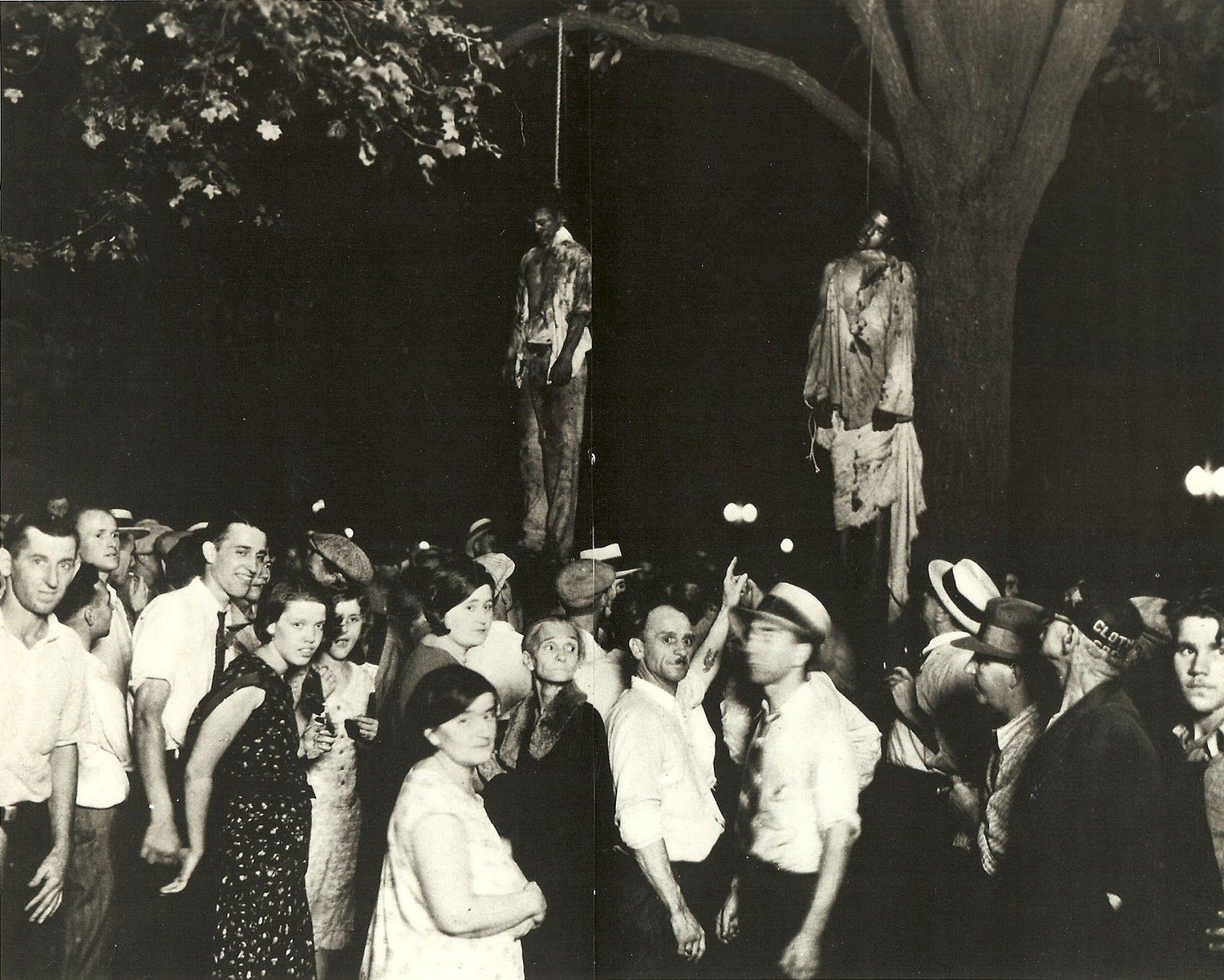

These last two images sent shivers down my spine and sparked memories of a childhood trip with my grandfather to Pulaski, Tennessee. This particular trip was part of an annual Labor Day tradition of visiting my great grandmother and other relatives who lived in this rural community along the Tennessee-Alabama border. I didn’t know it at the time, but Pulaski is the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan. I’m not even sure my grandfather, who did not receive formal education and remained illiterate his entire life, even knew this. But his lived experience made him very familiar with the Klan. After a memorable homemade country breakfast of fried chicken, billy goat, fried apples, fresh eggs, and hot biscuits, my grandfather asked me to join him on a walk down through the surrounding rolling hills. We stopped at a beautiful old tree that provided us some shade from the late summer sun. “Here,” my grandfather said, “on this spot, in this tree, my father was lynched by the Klan.”

At my young age, I could not fully understand what had actually transpired. Nor did I know, as I eventually learned as a college undergraduate, how my great grandfather’s murder was part of a late 19th and early 20th-century epidemic of ritualized lynchings of Black men and women that served to reinforce the political, economic, and social boundaries of white supremacy that had been destabilized by Emancipation and Reconstruction. Nonetheless, I could see the pain and anger on the face of my generally amiable-looking grandfather. And over time, as I heard stories of crosses burning on hilltops and back-breaking work behind a mule plow, I came to understand the terror and toil that lead my grandfather and millions of African Americans to make their way to the north as part of the Great Migration of the early 20th Century. Little did my grandfather know that the Klan beat him to Indiana where it had infiltrated state government at the highest levels including the governorship.

At my young age, I could not fully understand what had actually transpired. Nor did I know, as I eventually learned as a college undergraduate, how my great grandfather’s murder was part of a late 19th and early 20th-century epidemic of ritualized lynchings of Black men and women that served to reinforce the political, economic, and social boundaries of white supremacy that had been destabilized by Emancipation and Reconstruction. Nonetheless, I could see the pain and anger on the face of my generally amiable-looking grandfather. And over time, as I heard stories of crosses burning on hilltops and back-breaking work behind a mule plow, I came to understand the terror and toil that lead my grandfather and millions of African Americans to make their way to the north as part of the Great Migration of the early 20th Century. Little did my grandfather know that the Klan beat him to Indiana where it had infiltrated state government at the highest levels including the governorship.

Like my grandfather, George Floyd migrated to the North looking for a better quality of life and improved life chances. Like my great grandfather, George Floyd was lynched. It does not matter that there was no lynching tree. The agonizing and slow-motion murder of George Floyd filled me with rage and anguish, leaving me feeling traumatized as did the January 6 assault on our democracy. I’ve been dealing with this for quite a long time. Almost a hundred years after the lynching of my great grandfather, I found myself deliberating whether or not I should take my 9-year-old daughter to the site, just a few miles from our home, where George Floyd’s life was crushed by a police officer’s knee, concrete pavement, and anti-blackness. African Americans have been dealing with this for much too long.

In his 1964 Nobel Prize speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. reflected hopefully, “I believe that wounded justice, …… lying prostrate on the blood flowing streets of our nation can be lifted from the dust of shame to reign supreme . . . when our days become dreary with low hovering clouds and our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, we will know that we are living in the creative turmoil of a genuine civilization struggling to be born.” As we emerge from one of the most vulnerable and darkest moments in our democracy’s history, it is important to remind ourselves that the (r)evolutionary leaps in our democracy have always been painful. The Black Freedom Movement teaches us that the struggle for transformative justice has always generated a backlash. It also teaches us that if we can find the strength to love and the courage to engage in the soul-growing work of healing justice, we can recover from spiritual death, moral bankruptcy, and racialized oppression.

In his 1964 Nobel Prize speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. reflected hopefully, “I believe that wounded justice, …… lying prostrate on the blood flowing streets of our nation can be lifted from the dust of shame to reign supreme . . . when our days become dreary with low hovering clouds and our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, we will know that we are living in the creative turmoil of a genuine civilization struggling to be born.” As we emerge from one of the most vulnerable and darkest moments in our democracy’s history, it is important to remind ourselves that the (r)evolutionary leaps in our democracy have always been painful. The Black Freedom Movement teaches us that the struggle for transformative justice has always generated a backlash. It also teaches us that if we can find the strength to love and the courage to engage in the soul-growing work of healing justice, we can recover from spiritual death, moral bankruptcy, and racialized oppression.

We must not let the darkest moments of the last year, or last 400 years, blind us to the thread of ancestral light that shimmers in the present. Kamala Harris is our nation’s first female Vice President. She is a woman of color, the daughter of immigrants from India and Jamaica. On stage with her at the Inauguration was our nation’s first African American President and First Lady. In the wake of the death of their U.S. Representative John Lewis, one of our nation’s civil rights icons, Georgia elected its first African American and Jewish Senators. Senator Warnock had been serving as pastor of the historic Ebenezer Baptist church once led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. While in high school, Jon Ossoff interned with U.S. Representative John Lewis.

African Americans have gifted the United States a cultural, ethical, and political inheritance that highlights a path toward restorative justice, collective healing, and greater human freedom. All of us, not just African Americans, will need to learn to live with the inherited pain of our settler-colonial history for a long time if we are to truly make sense of it. And as so many yearn to get back to a normal post-pandemic life, it is important to remember that normal is the very reality from which many of us as African Americans yearn to be free. That said, I hope that we can, in the Sankofa spirit, take advantage of Black History Month to not only do the necessary grieving of all that has been lost to the world by the 400 hundreds of years of limiting the opportunities of African Americans but also to equip ourselves intellectually, culturally, and politically for the important work of reclaiming our humanity and progressing together toward a more genuine multicultural democracy.