The Power of Poetry to Heal

Authored By: wells438 01/19/2024

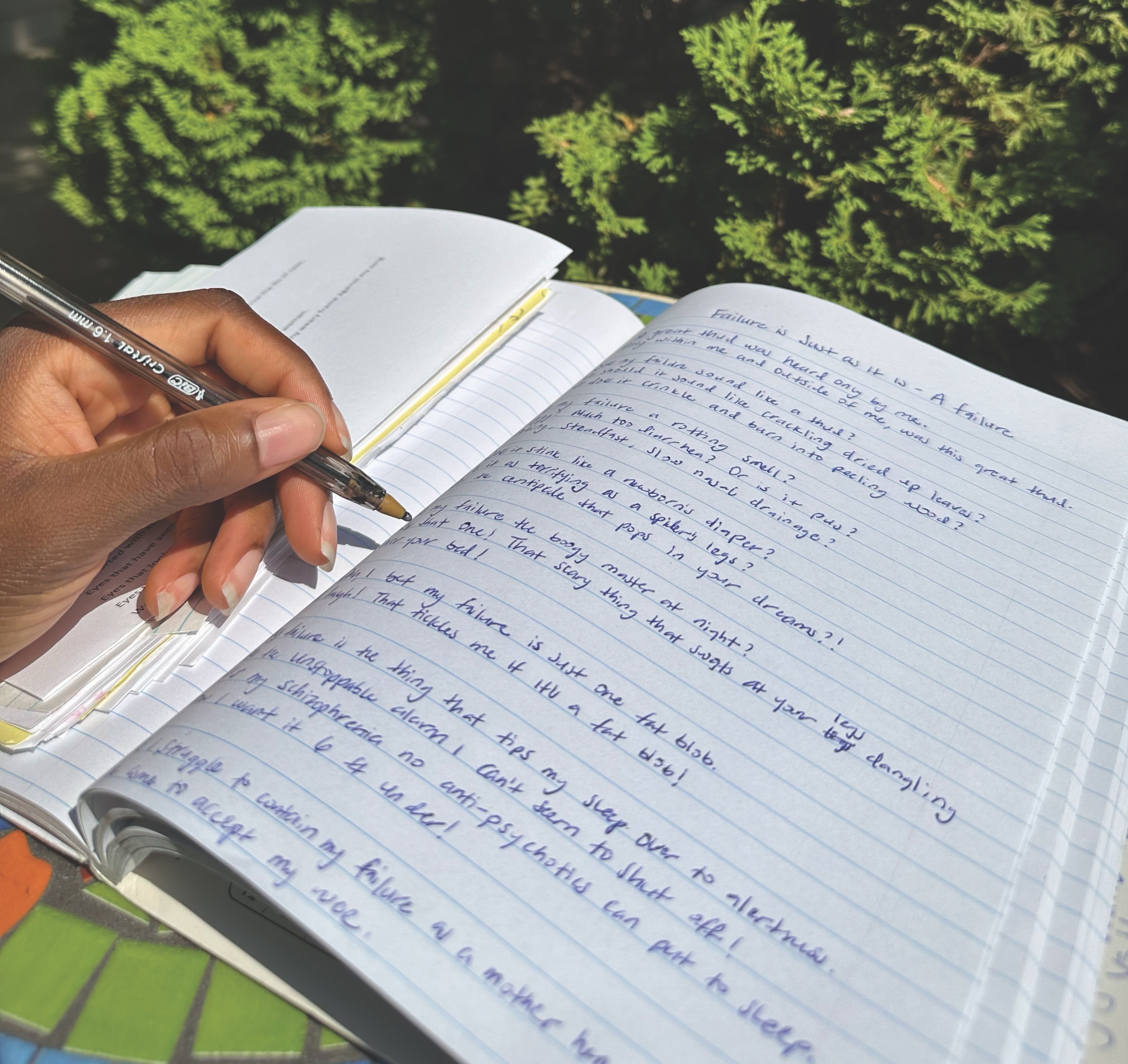

UMR alumna Amarachi Orakwue ’19 discovered her love of poetry in an eighth-grade creative writing class. “Our teacher gave us an assignment to write a poem. I remember writing mine. It was very easy to write. I brought it to class and my teacher read it. She was the first person to call me a poet.”

The experience changed the course of Amarachi’s life, inspiring her to pursue a life as both an artist and a health care provider dedicated to helping others heal.

At the time of her eighth-grade epiphany, Amarachi had just immigrated to Minnesota from Nigeria with her parents, younger sister and brother. “It was pretty chaotic being in a new country, not understanding the culture, feeling isolated and different. Poems were a way for me to understand what was going on and my emotions. It was a way to befriend my thoughts. I loved how paper was blank, an open space for me to fill up with whatever was in my mind. I loved the privacy of paper. I could be very vulnerable.”

She created a book of poetry, which she kept private and close to her heart for many years.

Amarachi’s family moved often in those early years before landing in Rochester. She completed her senior year at Century High School, where she discovered her love of the sciences, particularly chemistry. She initially wanted a career in pharmacy, and UMR was the perfect fit for key reasons. “It has small class sizes and more time to meet with teachers. It’s geared to students going into medical professions and close to Mayo Clinic.”

She enrolled at UMR in 2016 as a member of the inaugural Health CORE (Community of Respect and Empowerment) living learning community, an initiative brought to life by Chancellor Lori Carrell. The first group of 30 students came from communities underrepresented in higher education — first generation college students, Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC), low income — to create a diverse group committed to living and learning together, celebrating and supporting one another.

“It was a spectacular group of young people,” Chancellor Carrell recalls. “They came from many backgrounds, languages and religions, but they had a golden thread that wove them together: They wanted to make a difference in the world through a career in health.”

The incoming class had the chance to showcase the catalysts for their passion — and demonstrate their civic commitment — with a three-minute presentation at a rigorous scholarship competition. At the event, a supportive audience of scholarship benefactors were present, including Joe and Peggy Marchesani. The Marchesanis had established a scholarship in memory of Joe’s mother, Katherine Guarino Marchesani. The scholarship had much of the usual criteria, plus the novel requirement that the recipient be a poet. “My mother loved poetry, and well past her 100th birthday could recite poems she had learned in grade school,” says Joe. “We believe that an appreciation for the arts, such as poetry and music, makes someone trained in the medical sciences a more rounded, sensitive and empathetic person.”

The scholarship had not been awarded for a number of years, until Amarachi performed her poetry at the competition and her secret gift as a poet was revealed.

Chancellor Carrell — whose first discipline is communication and the study of the spoken word — reached out to Amarachi.

“We first bonded over our love of words,” Amarachi says of the Chancellor. “In her office, she has a jar of words for people to pick a paper with the word of the day. She had seen me perform the poem and reached out to me about it.

The Chancellor told Amarachi about the scholarship, and that Joe and Peggy would like to meet her for lunch. She brought along the poetry book she had created in middle school. “I showed it to Joe and Peggy. I had all these poems I had been writing for so long. We talked about poetry, ourselves. We bonded over that lunch.”

That day, Amarachi received more than the scholarship — she received lifelong friends, mentors and supporters of her passion for both poetry and health care.

“Peggy and Joe have always encouraged me to publish my poetry. Without them I wouldn’t ever consider it. It can be easy for us to not take notice of our own talents. They showed me it can be a powerful gift, and to try to share it with the world.”

She also credits the Marchesanis and Chancellor Carrell for helping her see poetry as a way to bring awareness of societal issues to the world at large. While at UMR, she and some classmates began an annual poetry event for Black History Month at a Rochester coffee shop, open to all community members to come and share. During the pandemic, the event continued virtually, and people from all over the country attended. “Poetry allows the opportunity for us to learn each other’s stories,” she says. “We find, when we’re done, an atmosphere of love, support, peace and harmony.”

After George Floyd’s death in 2020, Amarachi worked with Barbara Jordan, a member of the Rochester NAACP, to hold a vigil in the Rochester community. At the vigil, she read her poetry and saw in a new light the power of poetry to uplift community voices.

Chancellor Carrell observed how the spoken word became a powerful part of Amarachi’s anti-racism leadership. “She spoke in new ways, in new venues, with new strength. She was truly an inspiration for many.”

While a member of the Health CORE community, Amarachi was surrounded by students from many different health care fields, and they helped her find her calling to medicine. “I had friends I trusted. They would talk about why they loved medicine. And I would say why I loved pharmacy. I wanted to manage the whole care plan for a patient. And they’d say, that sounds more like a physician.”

A health professions summer education program in Florida sealed the deal for her, and she switched to pre-med. She is currently a third-year medical student at the University of Minnesota Medical School, interested in obstetrics and gynecology.

“Now I’m thinking of how to bring poetry into medicine,” she says. “I want to go into visual poetry and short films and allow other people to share in these poems. I’m interested in talking to women who have felt unheard — Black women — and how that has led to them losing their child or having complicated pregnancies.”

Poetry will continue to serve Amarachi in her role as a health care provider, says Chancellor Carrell. She cites research on creativity contributing to the resilience and well-being of health care professionals. “The role of creativity and humanities is central. If a studious person who is very committed to others, like our students, only focuses on studies to the exclusion of what it means to be human, they are less likely to be well. Building resilience by having a means of expression is critical to the health of our health professionals. The well-being of our health professionals matters to all of us.”

Amarachi shares how poetry makes her more empathetic with her patients. “Poetry channels the emotional part of us. When we come into the hospital and talk to patients, they can see our humanity — that is empathy. Because we are able to process our own feelings of sadness and joy, when we see it in someone else, we can allow them to express it. At that moment, we can connect with them.”

Further, she says, this deep connection leads to improved patient care and outcomes. She recalls a significant turning point between herself and a patient. “A patient came in and they were not taking their medication. In that moment, I could connect as a human being and ask why? They shared their feelings, and they were feelings I had had — hopelessness, fear, frustration. I told them, I can’t understand what it is to be in your shoes, but I can empathize with you. They got emotional. They told me more, something not in their chart history. Connecting in that moment actually helped solve the problem. Connecting on the level of humanity is healing.”

Read more stories from the Fall 2023 Alumni Magazine: The Kettle.